MOMENT OF TRUTH

The winds of change are blowing. After months of hardscrabble activism—five community meetings, three letters to the people, and two local newspaper articles—an actual tornado hit the Oregon coast just a couple of miles from Nehalem. 128 homes and hundreds of trees were damaged or destroyed last week. While people rebuild their houses and businesses, the future of our community hinges on Nehalem's mayoral race. Will this town elect me, a populist newcomer, to navigate the changes already underway?

Frankly, no one knows. And that is a fundamental departure from tradition. Political power in Nehalem has always been uncontested: elections are not really elections. But not this time—and possibly never again.

On one front, we have already won: the people are now demanding responsive government. My opponents have lashed out with juvenile gossip and ineffective bullying. For a taste of the mood in Nehalem, please read and share this article, published today on Fusion.

In these final days before the vote, let's pray that the storm of change sweeps away all fear, clearing the ground for the rebuilding of democracy.

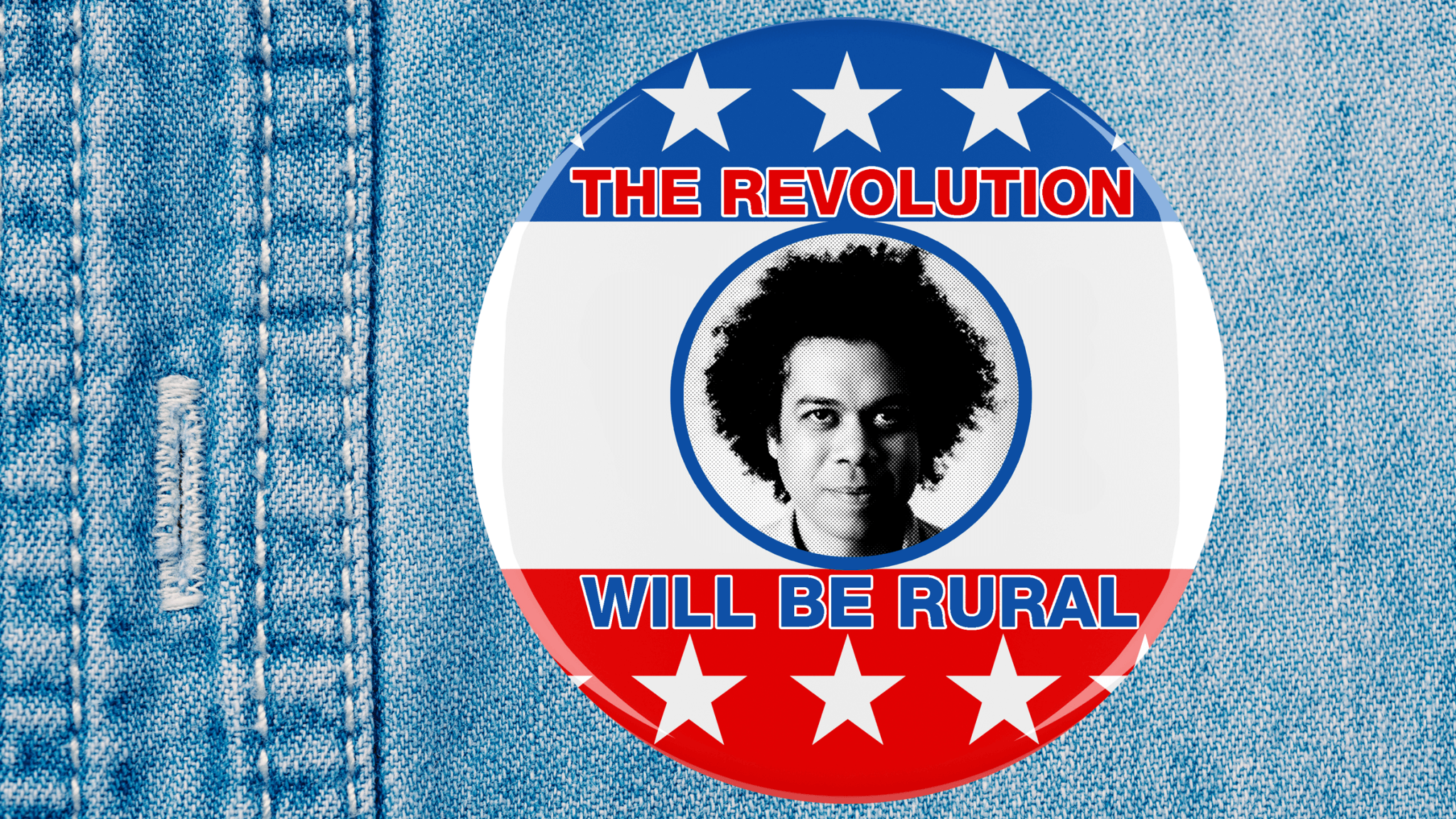

— Micah White

How to bring a revolution to rural Oregon

Written by Donnell Alexander for Fusion

The lights in the rec center community room burn through mid-afternoon. Fifteen people sit in a broad circle, hunched forward atop mismatched furniture on this October Sunday. Some at this town hall, put on by the new Nehalem People’s Association, take notes. Others speak with passion. Only occasionally do overlapping voices devolve into crosstalk.

The shapeless-yet-compelling colloquy pings back to its unlikely leader: Brown-skinned, with wiry long hair and a willowy effect, 34-year-old Micah White looks exactly like the kind of guy who would schedule a rural American town hall at the same time as some of the big NFL matchups are playing on TV.

White wants to discuss a parcel of land that may be up for development, but he waits for the attendees to come upon the subject’s relevance on their own. Nehalem, like many parts of the country with a heavy tourist presence, struggles to balance long-time residents with seasonal visitors, in addition to other woes. A strata of impoverished Tillamook County residents is said to live in the nearby forest year-round, roughing it. And a popular nearby pizzeria recently discontinued dine-in service because it couldn’t summon enough workers to sustain people eating in. There isn’t enough housing in tiny Nehalem to go around.

Outside the town hall, drizzle falls over lush greenery, because it is October in the densely forested, intoxicatingly beautiful Pacific Northwest. One jarring element, new this offseason, are the lawn signs touting the mayor’s reelection campaign. They are the first campaign materials many Nehalem old-timers can remember ever seeing in this small former logging town.

A quarter-mile burg whose median age is 52—12 years older than the rest of Oregon—Nehalem isn’t used to activism. Its natives and Portland retirees have been more about hunting and crabbing and the small-town gossip (as observed in that Everclear song named after the place) than the talk this guy with his Ph.D. from Switzerland has been pushing.

One sees the signage and wonders: Is City Hall fighting Micah White?

Not exactly. But the radical is running for mayor.

A lifelong activist who transformed an editing position at the Vancouver-based, anti-consumerist magazine Adbusters into a founding role in Occupy Wall Street’s formation, White hardly hides that his political activity in Nehalem functions as a testing ground for the ideas from his “playbook for revolution,” which was published last spring. In The End of Protest, White advocates moving “ruthless innovation” into municipalities such as this—Nehalem has 180 registered voters—so that issues such as wealth inequality, affordable housing and general citizen sovereignty might take hold, then go viral.

The season’s game plan is to utilize the Nehalem People’s Association as a vessel of direct democracy, thereby taking over the somnolent Nehalem government, establishing a springboard for like-minded people to flood rural America and set up copycat actions of their own.

God brought Micah White to Nehalem—a place meaning “place where the people live”—he told me. The former atheist says that after Occupy Wall Street’s “constructive failure” he and many of his fellow change agitators were at extreme loose ends. Some collaborators got divorces, some became deeply lost. Malaise was ruling the day. But while traveling with his spouse, Chiara Riccardone, the then-Berkeley resident happened upon Nehalem Bay State Park. The awe of the place, ocean and bay and fir, knocked them for a loop. Malaise evolved to something like an opportunity. They moved to the northern corner of Oregon’s coast shortly thereafter.

“What I’m trying to do is solve the problems that plagued Occupy,” White says. Theoretical revolution was not going not going to provide verifiable impact on the lives of people making an average $47,000 per year in a region priced for tourists.

“Income inequality in Nehalem has manifested in a socio-political inequality where only certain social groups feel comfortable running for office,” White says outside the town hall. Further compounding the difficulty of democratic representation, observes White, is the town zoning, which places less wealthy Nehalem residents who live in residential trailers outside of city limits and therefore unable to fully participate in city council activities. “The problems that are faced here are faced everywhere,” he tells me. “That’s why I like this place.”

🌲 🔨 🌲

White is an inveterate provocateur. As a 13-year-old student he made his first protest, against his school’s mandatory National Anthem policy, got attention, and hasn’t stopped since. He spearheaded civil disobedience against voting machine maker Diebold, as a Swarthmore College undergrad. Then came Occupy.

A newcomer in rural government, where how deep one’s roots go might count as much as how much money a person has, White is flagrant in treating his campaign as an experiment based on his writing. He uses words like “revolution” and “takeover” despite visible and intense displeasure on the part of the neighbors he says he aims to empower. And all this is happening in a part of remote, white America, in which being an adult black male briskly rounding an aisle in the grocery store is enough to startle another shopper.

Nehalem, population 271, is the middle village in a trio of tiny municipalities in Tillamook County that make their bones off vacationers. There are five realty offices on neighboring Manzanita’s main street, and the perils of residents in search of affordable housing seem to grow with each flipped vacation property. Airbnb has more listings for Nehalem then there are actual 155 residences in the town proper, offering up stays for an average of $211. County residents bemoan “the Portlandia effect,” but their trouble looks more to be peer-to-peer marketplace than man-buns.

Coming up repeatedly in the waves of Sunday’s town hall talk was a plot of land owned by Dan Conner, a Southern California developer who keeps a luxurious second home in Manzanita. Most residents are in the dark about the land parcel’s future, but a sketch on the county’s website suggests offices for lawyers and, yes, more realtors.

The attendees at the town hall float a few half-formed alternatives to this plan: namely affordable housing. Because local inexpensive housing is virtually nil, the vacation industry’s outsize pool of restaurant workers and housekeepers often commutes 25 miles both ways, on winding, mostly rainy roads. Children native to Nehalem turn 18, then leave; there’s no housing available near their families for them to stay.

A renting San Diego transplant named Paula observes that while many vacation rental properties sit empty all year, “There are people in need of housing. It doesn’t make sense to me.”

Here and there graying homeowners pick apart the notion of addressing the “Conner corner” at the next night’s City Council meeting. No one asks questions at Nehalem City Council meetings, and few qualms are shown about taking Mayor Bill Dillard at his word. His father was also mayor, after all. But as the colloquy toggles awkwardly between this talk, just one bit is clear: Even Micah White’s most sympathetic supporters in this place of constant beauty eye him with a degree of unease. Dude’s only been here four years.

The End of Protest, White’s book, was published by Knopf Canada in March. The scholarly volume offers an intellectually untethered perspective on the potential of what some of us call Cascadia. “The land is rich in natural resources and priceless biodiversity,” it reads. It is “rugged, wild, porous, and therefore difficult to police … Secessionist movements enjoy moderate public sympathy. Local police are few and likely to be loyal to the people.”

Through coffee shop chat, I learned that Nehalem residents have read The End of Protest. A local school official told me he did so without alarm. This text is not what began the divisions. Friction began with White’s first letter to prospective voters. Before Dillard had yard signs, Micah White put out a direct mailing.

In it, he first cited Scripture—Proverbs 29:19: “Where there is no vision, the people perish”—then lodged a complaint about council appointments, calling the process “undemocratic,” the council “unimaginative,” the situation “unfortunate. Worse, it is dangerous.” The existing political establishment of five council members, mayor, city manager, and, most importantly, the local merchants’ association was blindsided by White’s letter.

This generated a relative avalanche of fiery, bitter discussion of the letter’s substance on Facebook and an online dissection of local issues. Then came a huge turnout, roughly 60 people, for White’s first Nehalem People’s Association town hall in August. Among the activists and curious residents were flat-out angry glarers. Some were drunk, according to sources. The brother of a well-known city worker sported a Confederate flag shirt. A mysterious short-haired stranger dressed in black fumed throughout the event, before announcing “Fuck this shit!” and walking out.

🌲 🔨 🌲

The night after Sunday’s town hall, about five times more citizens than usual are inside the Nehalem City Council chambers for the body’s monthly meeting. The council doesn’t at all seem a dastardly lot. On the wall to the left of the officials’ platform is an epic quilt made up of river blues and verdant firs that reflects the history and interests of this crabbing-enamored town:. To the right is a portrait of the late Mayor Shirley Kalkhoven, who presided for two decades before passing away last year at 87. Dale Stockton took her place, but then his mind began to slip. When he stepped aside, the current Mayor Bill Dillard was slotted in.

Dillard, a 15-year council vet, declined requests to be interviewed for this article. (“I’m not going to help get his name out there,” he said about White.) He seems a laconic sort, at least in contrast with Dale Schafer, Nehalem’s city manager. Schafer—who just happened to be in realty when she began running the town—would come off as boss even if she never opened her mouth.

Candy dishes and nameplates sit before Dillard and Schafer, her assistant, and the other commissioners—one of whom makes a living minding empty vacation homes.

The law enforcement report is admitted to the record—one arrest last month. Only one other item of old business: Dan Conner’s lot. No discussion is scheduled on the rare piece of open Nehalem land. Some in the public suspect a backroom deal, business as usual. Micah White raises his hand, waits a while.

“Will there be a public meeting?”

“I’m very hesitant to have the public tell a private person what to do,” Mayor Dillard says.

Annoyed, the city manager says she hasn’t even seen a full proposal, and won’t consider the matter until she does.

“It will be discussed at that time,” she tells White. She reminds the public there’s only a rendering of the proposed development on the lot as of now.

“I get it,” White says.

“I don’t know if you do,” shoots back council member Jeff Pfeifer.

“Don’t talk down to me,” White counters.

Then, Brenna Hamer, owner of a business downtown, explains that she’s shown up on a whim and seizes the seemingly unprecedented opening to begin to articulate her vision for the lot: nature and art that project the charm and friendliness of the town.

“What Dan [Conner] is proposing is kind of what I was hoping wouldn’t happen,” Hamer says.

From there, public input is on. The Council meets about twice as long as usual. Development at the Connor corner won’t be rammed down the people’s throat. The wheels of participatory democracy start turning.

At the end of the city council meeting, local council candidate Lucy Brook, a 74-year-old retired coffeehouse owner, connects with a retired person from Sunday’s town hall. They begin preliminary strategizing on how to deal with the “gap-toothed, trailer park” poverty that goes unseen. (The region just built its first homeless resource, a “warming center,” almost a half hour down Highway 101.) Something is happening here. Election or nah, that connection just happened, instead of another Nehalem City Council meeting that smacked of transactions already done.

And even I am made uncomfortable by the daggers being stared at me from behind the dais of elected officials.

In these tense times, what if it is true that in our tangible future, we have an option that’s distinctly post-protest? That regular citizens can have a say in how a small, remote parcel of land controlled by a faraway interest suggests a participatory democracy capable of actually delivering decision making and power to the people. The aging landscaper concerned about where she’ll lay her head 18 months from now and the parent who just wants nearby shelter for his daughter could have the same clout as a mayor or a lobbyist or a well connected realtor, particularly in these smalls towns.

Will the relevance of White’s gambit prove as durable as La Raza Unida’s takeover of government in Crystal City, Texas? Can his political visibility and playbook for revolution gain the same traction as, say, progressive movement’s darling, Pennsylvania mayor, John Fetterman? The answer depends on the people of this sleepy Cascadian town on election day. Nevermind the future though; the simple genius of merging into the least clogged political lane and then generating progress has mesmerizing real-time consequences.

“We can have endless protests like [Colin Kaepernick] and endless Black Lives Matters marches in the streets, endless Occupys going into squares,” White told me. “And it would get all of the media coverage that you want, but this is revolutionary: Trying to take control of a city council in a small town and then give the power to people who meet as the Nehalem People’s Association.”

This article was originally published by Fusion.

Learn more about Micah White's vision of the future of activism in his new book, The End of Protest: A New Playbook For Revolution.